“This is one of those ‘sit up and read very carefully’ moments,” said one science journalist.

By Julia Conley, Common Dreams

Scientists are so alarmed by a new study on ocean warming that some declined to speak about it on the record, the BBC reported Tuesday.

“One spoke of being ‘extremely worried and completely stressed,'” the outlet reported regarding a scientist who was approached about research published in the journal Earth System Science Data on April 17, as the study warned that the ocean is heating up more rapidly than experts previously realized—posing a greater risk for sea-level rise, extreme weather, and the loss of marine ecosystems.

Scientists from institutions including Mercator Ocean International in France, Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the United States, and Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research collaborated to discover that as the planet has accumulated as much heat in the past 15 years as it did in the previous 45 years, the majority of the excess heat has been absorbed by the oceans.

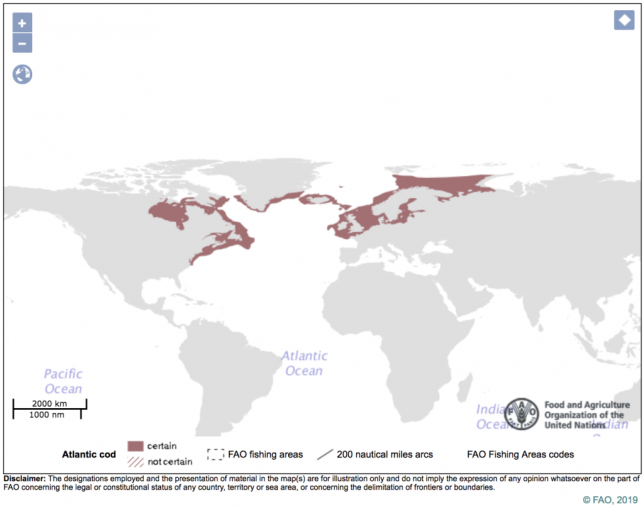

In March, researchers examining the ocean off the east coast of North America found that the water’s surface was 13.8°C, or 24.8°F, hotter than the average temperature between 1981 and 2011.

The study notes that a rapid drop in shipping-related pollution could be behind some of the most recent warming, since fuel regulations introduced in 2020 by the International Maritime Organization reduced the heat-reflecting aerosol particles in the atmosphere and caused the ocean to absorb more energy.

But that doesn’t account for the average global ocean surface temperature rising by 0.9°C from preindustrial levels, with 0.6°C taking place in the last four decades.

The study represents “one of those ‘sit up and read very carefully’ moments,” said former BBC science editor David Shukman.

This is one of those ‘sit up and read very carefully’ moments: the #ocean is warming at a phenomenal rate and the consequences will be severe. Great reporting by @MattMcGrathBBC and @MarkPoynting https://t.co/7vnqlVD4La

— David Shukman (@DavidShukman) April 25, 2023

Lead study author Karina Von Schuckmann of Mercator Ocean International told the BBC that “it’s not yet well established, why such a rapid change, and such a huge change is happening.”

“We have doubled the heat in the climate system the last 15 years, I don’t want to say this is climate change, or natural variability or a mixture of both, we don’t know yet,” she said. “But we do see this change.”

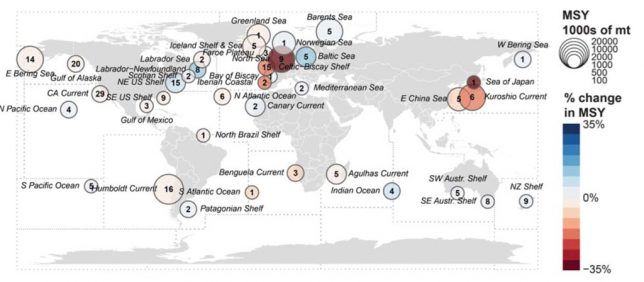

Scientists have consistently warned that the continued burning of fossil fuels by humans is heating the planet, including the oceans. Hotter oceans could lead to further glacial melting—in turn weakening ocean currents that carry warm water across the globe and support the global food chain—as well as intensified hurricanes and tropical storms, ocean acidification, and rising sea levels due to thermal expansion.

A study published earlier this year also found that rising ocean temperatures combined with high levels of salinity lead to the “stratification” of the oceans, and in turn, a loss of oxygen in the water.

“Deoxygenation itself is a nightmare for not only marine life and ecosystems but also for humans and our terrestrial ecosystems,” researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration said in January. “Reducing oceanic diversity and displacing important species can wreak havoc on fishing-dependent communities and their economies, and this can have a ripple effect on the way most people are able to interact with their environment.”

The unusual warming trend over recent years has been detected as a strong El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is expected to form in the coming months—a naturally occurring phenomenon that warms oceans and will reverse the cooling impact of La Niña, which has been in effect for the past three years.

“If a new El Niño comes on top of it, we will probably have additional global warming of 0.2-0.25°C,” Dr. Josef Ludescher of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research told the BBC.

The world’s oceans are a crucial tool in moderating the climate, as they absorb heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gases.

Too much warming has led to concerns among scientists that “as more heat goes into the ocean, the waters may be less able to store excess energy,” the BBC reported.

The anxiety of climate experts regarding the new findings, said the global climate action movement Extinction Rebellion, drives home the point that “scientists are just people with lives and families who’ve learnt to understand the implications of data better.”