By Jonathan Levy, The Conversation

Cooks love their gadgets, from countertop slow cookers to instant-read thermometers. Now, there’s increasing interest in magnetic induction cooktops – surfaces that cook much faster than conventional stoves, without igniting a flame or heating an electric coil.

Some of this attention is overdue: Induction has long been popular in Europe and Asia, and it is more energy-efficient than standard stoves. But recent studies have also raised concerns about indoor air emissions from gas stoves.

Academic researchers and agencies such as the California Air Resources Board have reported that gas stoves can release hazardous air pollutants while they’re operating, and even when they’re turned off. A 2022 study by U.S. and Australian researchers estimates that nearly 13% of current childhood asthma cases in the U.S. are attributable to gas stove use.

Dozens of U.S. cities have adopted or are considering regulations that bar natural gas hookups in new-construction homes after specified dates to speed a transition away from fossil fuels. At the same time, at least 20 states have adopted laws or regulations that prohibit bans on natural gas.

On Jan. 9, 2023, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission announced that it will consider measures to regulate hazardous emissions from gas stoves. The agency has not proposed specific steps yet, and said that any regulation will “involve a lengthy process.” On Jan. 11, CPSC Chair Alexander Hoehn-Saric further clarified that the agency was looking for ways to reduce indoor air quality hazards, but did not plan to ban gas stoves.

As an environmental health researcher who does work on housing and indoor air, I have participated in studies that measured air pollution in homes and built models to predict how indoor sources would contribute to air pollution in different home types. Here is some perspective on how gas stoves can contribute to indoor air pollution, and whether you should consider shifting away from gas.

Respiratory effects

One of the main air pollutants commonly associated with using gas stoves is nitrogen dioxide, or NO₂, which is a byproduct of fuel combustion. Nitrogen dioxide exposures in homes have been associated with more severe asthma and increased use of rescue inhalers in children. This gas can also affect asthmatic adults, and it contributes to both the development and exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Nitrogen dioxide in homes comes both from outdoor air that infiltrates indoors and from indoor sources. Road traffic is the most significant outdoor source; unsurprisingly, levels are higher close to major roadways. Gas stoves often are the most substantial indoor source, with a greater contribution from large burners that run longer.

The gas industry’s position is that gas stoves are a minor source of indoor air pollutants. This is true in some homes, especially with respect to exposures averaged over months or years.

But there are many homes in which gas stoves contribute more to indoor nitrogen dioxide levels than pollution from outdoor sources does, especially for short-term “peak” exposures during cooking time. For example, a study in Southern California showed that around half of homes exceeded a health standard based on the highest hour of nitrogen dioxide concentrations, almost entirely because of indoor emissions.

How can one gas stove contribute more to your exposure than an entire highway full of vehicles? The answer is that outdoor pollution disperses over a large area, while indoor pollution concentrates in a small space.

How much indoor pollution you get from a gas stove is affected by the structure of your home, which means that indoor environmental exposures to NO₂ are higher for some people than for others. People who live in larger homes, have working range hoods that vent to the outdoors and have well-ventilated homes in general will be less exposed than those in smaller homes with poorer ventilation.

But even larger homes can be affected by gas stove usage, especially since the air in the kitchen does not immediately mix with cleaner air elsewhere in the home. Using a range hood when cooking, or other ventilation strategies such as opening kitchen windows, can bring down concentrations dramatically.

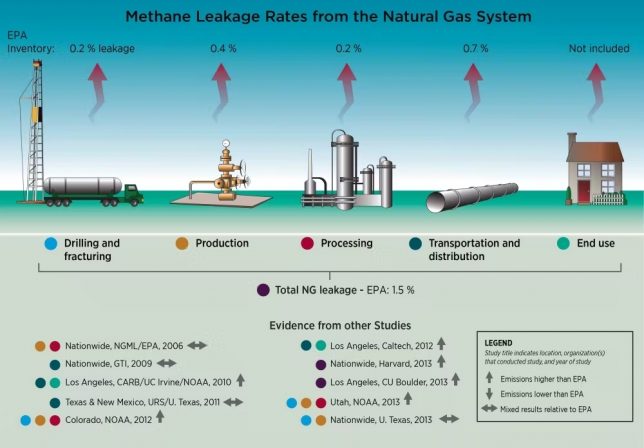

Methane and hazardous air pollutants

Nitrogen dioxide is not the only pollutant of concern from gas stoves. Some pollution with potential impacts on human health and Earth’s climate occurs when stoves aren’t even running.

A 2022 study estimated that U.S. gas stoves not in use emit methane – a colorless, odorless gas that is the main component of natural gas – at a level that traps as much heat in the atmosphere as about 400,000 cars.

Some of these leaks can go undetected. Although gas distributors add an odorant to natural gas to ensure that people will smell leaks before there is an explosion risk, the smell may not be strong enough for residents to notice small leaks.

Some people also have a much stronger sense of smell than others. In particular, those who have lost their sense of smell – whether from COVID-19 or other causes – may not smell even large leaks. One recent study found that 5% of homes had leaks that owners had not detected that were large enough to require repair.

This same study showed that leaking natural gas contained multiple hazardous air pollutants, including benzene, a cancer-causing agent. While measured concentrations of benzene did not reach health thresholds of concern, the presence of these hazardous air pollutants could be problematic in homes with substantial leaks and poor ventilation.

Reasons to switch: Health and climate

So, if you live in a home with a gas stove, what should you do and when should you worry? First, do what you can to improve ventilation, such as running a range hood that vents to the outdoors and opening kitchen windows while cooking. This will help, but it won’t eliminate exposures, especially for household members who are in the kitchen while cooking takes place.

If you live in a smaller home or one with a smaller closed kitchen, and if someone in your home has a respiratory disease like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, exposures may still be concerning even with good ventilation. Swapping out a gas stove for one that uses magnetic induction would eliminate this exposure while also providing climate benefits.

“I know people are hesitant about these kinds of induction stoves, but if you haven’t looked at one in 20 years, go take a look.” @evanhalper to a skeptical @GustavoArellano on the push by climate advocates to ditch gas stoves: https://t.co/NvZxqplO0E

— Sammy Roth (@Sammy_Roth) January 11, 2022

There are multiple incentive programs to support gas stove changeovers, given their importance for slowing climate change. For example, the recently signed Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which includes many provisions to address climate change, offers rebates for the purchase of high-efficiency electric appliances such as stoves.

Moving away from gas stoves is especially important if you are investing in home energy efficiency measures, whether you are doing it to take advantage of incentives, reduce energy costs or shrink your carbon footprint. Some weatherization steps can reduce air leakage to the outdoors, which in turn can increase indoor air pollution concentrations if residents don’t also improve kitchen ventilation.

In my view, even if you’re not driven to reduce your carbon footprint – or you’re just seeking ways to cook pasta faster – the opportunity to have cleaner air inside your home may be a strong motivator to make the switch.

This article has been updated to reflect the Jan. 11, 2023 statement from the Consumer Product Safety Commission that the agency has no plans to ban gas stoves.