“These currently elevated rates of ice melting may signal that those vital arteries from the heart of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet have been ruptured,” said one researcher. “Is it too late to stop the bleeding?”

By Julia Conley, Common Dreams (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

The human-caused climate crisis is pushing crucial glaciers in Antarctica to lose ice at a rate not seen in more than 5,000 years, according to a new study published Thursday.

Researchers at the University of Maine, the British Antarctic Survey, and Imperial College London found that the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers on the West Antarctic Ice Sheet could cause global sea level rise of up to 3.4 meters, or over 11 feet, in the next several centuries due to their accelerated rate of ice loss.

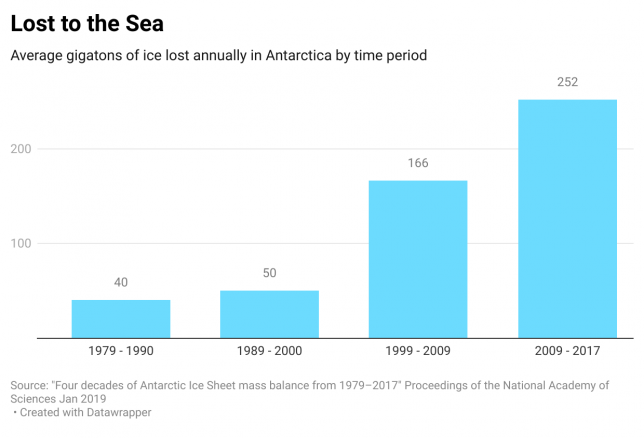

“That the present-day rate of glacier retreat that has doubled over the past 30 years is, indeed, unprecedented.”

The glaciers—one of which, the Thwaites, has been called the “doomsday glacier” by climate scientists because of its potential to raise sea levels—are positioned in a way that allows increasingly warm ocean water to flow beneath them and erode the ice sheet from the base, causing “runaway ice loss,” the University of Maine team said in a statement.

The researchers examined penguin bones and seashells on ancient Antarctic beaches in order to analyze changes in local sea levels since the mid-Holocene period, 5,500 years ago.

Sea levels were higher and glaciers were smaller during the mid-Holocene, as the climate of the planet was warmer than it is today.

Since then, according to the study published in Nature Geoscience, relative sea levels have fallen steadily and the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers have stayed relatively stable—until recent decades.

Ice loss was likely accelerated just prior to the mid-Holocene, and since then, the rate of relative decrease in sea levels over the past 5,500 years was almost five times smaller than it is in present day, due to “recent rapid ice mass loss,” according to the scientists.

“That the present-day rate of glacier retreat that has doubled over the past 30 years is, indeed, unprecedented,” wrote Caroline Brogan, a science reporter at Imperial College.

With the Thwaites spanning an area of more than 74,000 square miles and the Pine Island glacier spanning more than 62,600 square miles, the rapid ice loss of the two glaciers could cause major rises in sea levels around the globe.

Dylan Rood of Imperial College’s Department of Earth Science and Engineering, a co-author of the study, likened the two glaciers to arteries that have burst.

“These currently elevated rates of ice melting may signal that those vital arteries from the heart of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet have been ruptured, leading to accelerating flow into the ocean that is potentially disastrous for future global sea level in a warming world,” said Rood. “Is it too late to stop the bleeding?”

The study follows increasingly urgent calls from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Energy Agency, and climate scientists around the world for an end to fossil fuel extraction, which is needed to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and limit the average global temperature from rising more than 1.5°C above preindustrial levels.

Scientists have warned that the accelerated melting of the Thwaites glacier is likely irreversible.

“We’re going into unknown territory,” Scott Braddock, a researcher at University of Maine, told Science News. “We don’t have an analog to compare what’s going on today with what happened in the past.”