Plastic pollution has been found in practically every environment on the planet, with especially severe effects on ocean life. Plastic waste harms marine life in many ways – most notably, when animals become entangled in it or consume it.

We work as scientists and rehabilitators at The Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience and Sea Turtle Hospital at the University of Florida. Our main focus is on sea turtle diseases that pose conservation threats, such as fibropapillomatosis tumor disease.

However, it’s becoming increasingly hard to ignore evidence that plastic pollution poses a growing, hidden threat to the health of endangered sea turtles, particularly our youngest patients. In a newly published study, we describe how we examined 42 post-hatchling loggerhead sea turtles that stranded on beaches in Northeast Florida. We found that almost all of them had ingested plastic in large quantities.

An ocean of plastic

Ocean plastic pollution originates mostly from land-based sources, such as landfills and manufacturing plants. One recent study estimates that winds carry 200,000 tons of tiny plastic particles from degraded tires alone into the oceans every year.

Plastics are extremely durable, even in salt water. Materials that were made in the 1950s, when plastic mass production began, are still persisting and accumulating in the oceans. Eventually these objects disintegrate into smaller fragments, but they may not break down into their chemical components for centuries.

Overall, some 11 million tons of plastic enter the ocean each year. This amount is projected to grow to 29 million tons by 2040.

A microplastic diet

Many forms of plastic threaten marine life. Sea turtles commonly mistake floating bags and balloons for their jellyfish prey. Social media channels are replete with videos and images of sea turtles with plastic straws stuck in their nostrils, killed in plastic-induced mass mortality events, or dying after ingesting hundreds of plastic fragments.

So far, however, scientists don’t know a lot about the prevalence and health effects of plastic ingestion in vulnerable young sea turtles. In our study, we sought to measure how much plastic was ingested by post-hatchling washback sea turtles admitted to our rehabilitation hospital.

Post-hatchling washbacks are recently hatched baby turtles that successfully travel from their nesting beaches out to the open ocean and start to feed, but are then washed back to shore due to strong winds or ill health. This is a crucial life stage: Turtles need to feed to recover from their frenzied swim to feeding grounds hundreds of miles offshore. Feeding well also helps them grow large enough to avoid most predators.

We examined 42 dead washbacks, and found that 39 of them, or 93%, had ingested plastic – often in startling quantities. A majority of it was hard fragments, most commonly colored white.

One turtle that weighed 48 grams or 1.6 ounces – roughly equivalent to 16 pennies – had ingested 287 plastic pieces. Another hatchling that weighed just 27 grams, or less than one ounce, had ingested 119 separate pieces of plastic that totaled 1.23% of its body weight. The smallest turtle in our study, with a shell just 4.6 centimeters (1.8 inches) long, had ingested a piece of plastic one-fourth the length of its shell.

Consuming such large quantities of plastic increases the likelihood that broken-down plastic nanoparticles or chemicals that leach from them will enter turtles’ bloodstreams, with unknown health effects. Ingested plastic can also block turtles’ stomachs or intestines. At a minimum, it limits the amount of space that’s physically available for consuming and digesting genuine prey that they need to survive and grow.

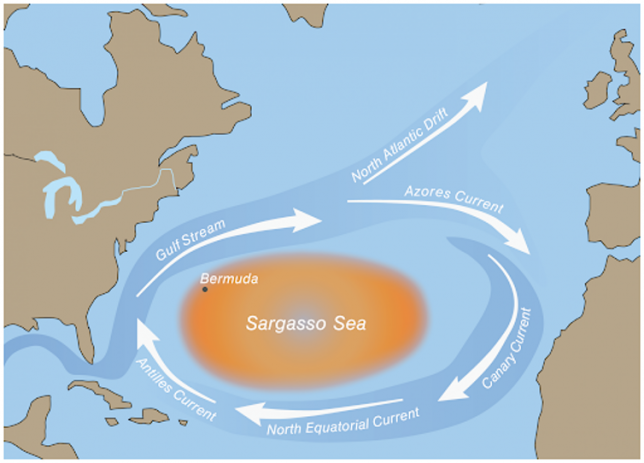

Turtles at this life stage live at the ocean’s surface, sheltering in floating mats of seaweed, where they feed on invertebrate prey such as zooplankton. These floating seaweed mats gather in the Atlantic, in an area known as the Sargasso Sea, which is bounded by four major ocean currents and covers much of the central Atlantic Ocean. The area is heavily polluted with plastic, as both seaweed and plastic travel on and are concentrated by the same ocean currents. Our study suggests that these baby turtles are mistakenly feeding on plastic floating in and around the seaweed.

Post-hatchling sea turtles are young and need to feed and grow rapidly. This means they are particularly at risk from the harmful consequences of ingesting plastic. We find it especially troubling that almost all of the animals we assessed had ingested plastic in such large quantities. Plastic pollution is only one of many human-related threats that these charismatic and endangered creatures face at sea.

Stemming the plastic tsunami

Since plastic persists for hundreds of years in the environment, clearing it from the oceans will require ingenious cleanup technologies, as well as lower-tech beach and shore cleanups. But in our view, the top priority should be curbing the rampant flow of plastic that is swamping oceans and coasts.

Earth’s ecosystems, especially the oceans, are interconnected, so reducing plastic waste will require global solutions. They include improving methods for recycling plastics; developing bio-based plastics; banning single-use plastic items in favor of more sustainable or reusable alternatives; and reducing shipment of plastic waste abroad to countries with lax regulatory regimes, from where it is more likely to enter the environment.

Our observations in post-hatchling turtles are part of a growing body of research showing how plastic pollution is harming wildlife. We believe it is time for humanity to face up to its addiction to plastic, before we find ourselves wading through swathes of plastic debris and wondering what went wrong.

David Duffy, Assistant Professor of Wildlife Disease Genomics, University of Florida and Catherine Eastman, Sea Turtle Hospital Program Coordinator, Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.