By Børge Brende, President, World Economic Forum (Public License).

World leaders are gathering in New York for the opening of the 77th session of the UN General Assembly and to discuss the major issues of the day. The list of agenda items is long.

The war in Ukraine continues to rage, energy markets are unstable, global temperatures are rising, and the COVID-19 pandemic lingers as other public health concerns emerge. Meanwhile, inflation has proved to be ubiquitous, burdening consumers, businesses, and governments worldwide.

To address these challenges, global leaders will likely stress the need for strengthening cooperation within, what the UN Secretary-General has called, today’s “fractured world”. The question is: at a time when fragmentation appears to be increasing, what can global cooperation, practically, look like?

Thankfully, we have examples. Because despite challenging headwinds, there are instances—pockets—of collaboration that are not only promising but offer insight into what makes cooperation possible, and even durable.

Fruitful collaboration tends to be characterised by three factors: the need is urgent, the area for collaboration is specific, and the benefits are clear.

Climate action is perhaps the most salient example of each of these.

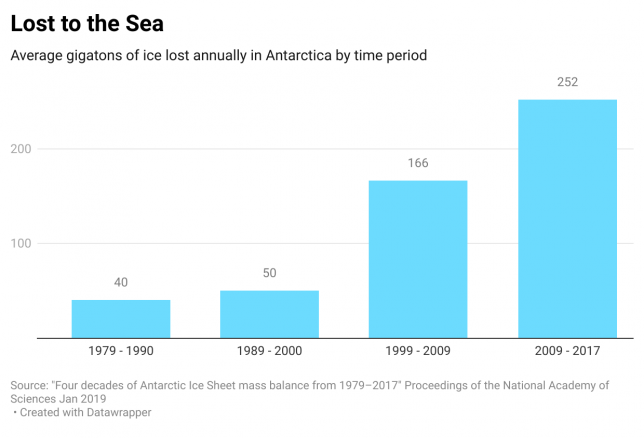

The urgency of addressing global warming is undeniable. Climate change is increasingly wreaking havoc worldwide, causing immense economic and human suffering. The devastating flooding in Pakistan is the latest example of lives being lost due to more intense weather patterns. This is why the UN raised the alarm earlier this year, stating in its latest climate report that the time for action to avoid catastrophic global warming is “now or never.”

As a result of the urgency, there are specific actions needed. World leaders have developed benchmarks that, if achieved in time, could mitigate the negative effects of climate change. This includes efforts to cut global greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030 and hit net-zero emissions by 2050. Such a reduction, experts hope, could limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. So far, over 70 countries, which account for 76% of global emissions, have created timelines for reaching net-zero.

And the benefits of collaborating on climate change are clear. We know the effects of a warming planet respect no border, so reaching our climate objectives can only happen when parties work together. Moreover, the transition to green energy systems—key to combatting climate change—is expected to generate over 10 million global jobs this decade.

All this is why 196 parties came together in 2015 to adopt the Paris Agreement and agreed last year at the UN Climate Conference in Glasgow (COP26) to increase carbon-cutting commitments.

Climate action also offers evidence that countries can compartmentalise and prioritise collaboration on a specific issue, despite disagreements elsewhere.

The United States and China, for instance, have shown a willingness to coordinate. Last year at COP26, the two countries issued a joint declaration that articulated the “seriousness and urgency of the climate crisis” and outlined areas in which both sides would take cooperative action.

More recently, at the World Economic Forum’s May 2022 Annual Meeting in Davos, US and Chinese climate envoys reaffirmed climate cooperation between their two countries. To be sure, this collaboration has hit road bumps, with talks recently suspended. But US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry has expressed hope they would resume because climate action “is the one area that should not be subject to interruption because of other issues that do affect us.”

It is also worth remembering that even during the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union coordinated environmental protection policies, specifically on guidelines around air and water pollution, environmental preservation and general mechanisms for tracking the changing climate.

Importantly, we do not need to wait on the side-lines for these three elements—urgency, specificity, and beneficial outcomes—to appear on their own. Instead, from tackling the COVID-19 pandemic to bolstering the global economy to unlocking the benefits of new technology, leaders can build momentum toward cooperation by identifying and advancing each of these elements.

There is one other factor that makes cooperation promising when it takes place. That is, inclusivity.

Partnerships between businesses, governments, and civic organizations are helping advance important efforts in battling climate change. Over 7,000 companies, 1,000 educational institutions and 1,000 cities have joined the UN-backed Race to Zero campaign to cut global emissions by 50% by 2030, which the World Economic Forum is helping advance. This type of widespread collaboration not only makes positive outcomes more likely but serves as a binding force among parties that improves durability.

Tackling the world’s challenges is no easy task. This is why we must remain on the lookout for early signs of where collaboration is possible—and shape the context so that it then becomes likely. The stakes are simply too high to allow disagreements elsewhere to hamstring progress around crucial issues.