Life as we know it can be sustained only if we preserve functioning ecosystems on at least half of planet Earth.

By Doug Tallamy, The Conversation (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

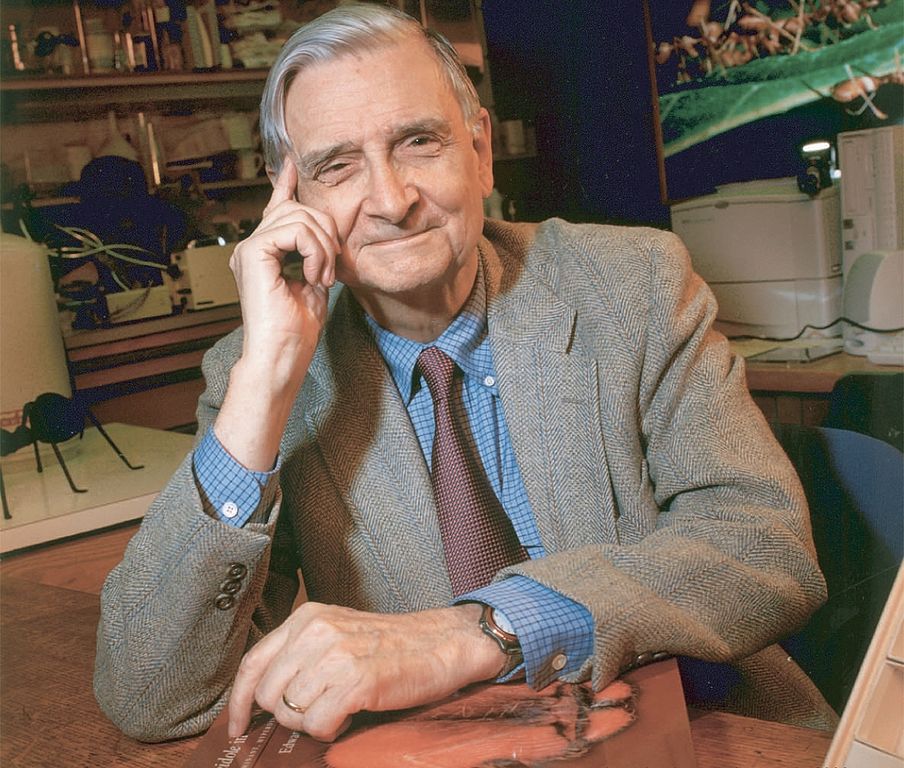

E. O. Wilson was an extraordinary scholar in every sense of the word. Back in the 1980s, Milton Stetson, the chair of the biology department at the University of Delaware, told me that a scientist who makes a single seminal contribution to his or her field has been a success. By the time I met Edward O. Wilson in 1982, he had already made at least five such contributions to science.

Wilson, who died Dec. 26, 2021 at the age of 92, discovered the chemical means by which ants communicate. He worked out the importance of habitat size and position within the landscape in sustaining animal populations. And he was the first to understand the evolutionary basis of both animal and human societies.

Each of his seminal contributions fundamentally changed the way scientists approached these disciplines, and explained why E.O.—as he was fondly known—was an academic god for many young scientists like me. This astonishing record of achievement may have been due to his phenomenal ability to piece together new ideas using information garnered from disparate fields of study.

Big insights from small subjects

In 1982 I cautiously sat down next to the great man during a break at a small conference on social insects. He turned, extended his hand and said, “Hi, I’m Ed Wilson. I don’t believe we’ve met.” Then we talked until it was time to get back to business.

Three hours later I approached him again, this time without trepidation because surely now we were the best of friends. He turned, extended his hand, and said “Hi, I’m Ed Wilson. I don’t believe we’ve met.”

Wilson forgetting me, but remaining kind and interested anyway, showed that beneath his many layers of brilliance was a real person and a compassionate one. I was fresh out of graduate school, and doubt that another person at that conference knew less than I — something I’m sure Wilson discovered as soon as I opened my mouth. Yet he didn’t hesitate to extend himself to me, not once but twice.

Thirty-two years later, in 2014, we met again. I had been invited to speak in a ceremony honoring his receipt of the Franklin Institute’s Benjamin Franklin Medal for Earth and Environmental Science. The award honored Wilson’s lifetime achievements in science, but particularly his many efforts to save life on Earth.

My work studying native plants and insects, and how crucial they are to food webs, was inspired by Wilson’s eloquent descriptions of biodiversity and how the myriad interactions among species create the conditions that enable the very existence of such species.

I spent the first decades of my career studying the evolution of insect parental care, and Wilson’s early writings provided a number of testable hypotheses that guided that research. But his 1992 book, “The Diversity of Life,” resonated deeply with me and became the basis for an eventual turn in my career path.

Though I am an entomologist, I did not realize that insects were “the little things that run the world” until Wilson explained why this is so in 1987. Like nearly all scientists and nonscientists alike, my understanding of how biodiversity sustains humans was embarrassingly cursory. Fortunately, Wilson opened our eyes.

Throughout his career Wilson flatly rejected the notion held by many scholars that natural history—the study of the natural world through observation rather than experimentation—was unimportant. He proudly labeled himself a naturalist, and communicated the urgent need to study and preserve the natural world. Decades before it was in vogue, he recognized that our refusal to acknowledge the Earth’s limits, coupled with the unsustainability of perpetual economic growth, had set humans well on their way to ecological oblivion.

Wilson understood that humans’ reckless treatment of the ecosystems that support us was not only a recipe for our own demise. It was forcing the biodiversity he so cherished into the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history, and the first one caused by an animal: us.

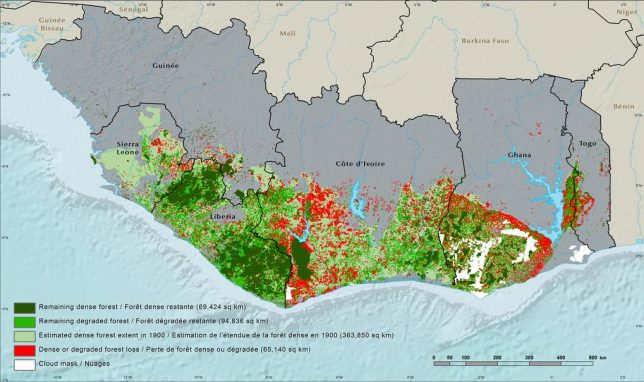

E.O. Wilson long advocated conserving the world’s biodiversity hot spots—zones with high numbers of native species where habitats are most endangered. This image shows deforestation from 1975 to 2013 in one such area, West Africa’s Upper Guinean Forest. USGS

A broad vision for conservation

And so, to his lifelong fascination with ants, E. O. Wilson added a second passion: guiding humanity toward a more sustainable existence. To do that, he knew he had to reach beyond the towers of academia and write for the public, and that one book would not suffice. Learning requires repeated exposure, and that is what Wilson delivered in “The Diversity of Life,” “Biophilia,” “The Future of Life,” “The Creation” and his final plea in 2016, “Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life.”

As Wilson aged, desperation and urgency replaced political correctness in his writings. He boldly exposed ecological destruction caused by fundamentalist religions and unrestricted population growth, and challenged the central dogma of conservation biology, demonstrating that conservation could not succeed if restricted to tiny, isolated habitat patches.

“Conservation is a discipline with a deadline.”

—Edward O. Wilson

In “Half Earth,” he distilled a lifetime of ecological knowledge into one simple tenet: Life as we know it can be sustained only if we preserve functioning ecosystems on at least half of planet Earth.

But is this possible? Nearly half of the planet is used for some form of agriculture, and 7.9 billion people and their vast network of infrastructure occupy the other half.

As I see it, the only way to realize E.O.’s lifelong wish is learn to coexist with nature, in the same place, at the same time. It is essential to bury forever the notion that humans are here and nature is someplace else. Providing a blueprint for this radical cultural transformation has been my goal for the last 20 years, and I am honored that it melds with E.O. Wilson’s dream.

There is no time to waste in this effort. Wilson himself once said, “Conservation is a discipline with a deadline.” Whether humans have the wisdom to meet that deadline remains to be seen.

Doug Tallamy is a professor in the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, where he has authored 103 research publications and has taught insect related courses for 40 years.