New approach reshapes markets by putting stewards of nature at the center.

By Ravi Prabhu, Steven Lawry, John Colmey, Forests News (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

“We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

—Aldo Leopold, American conservationist and forester

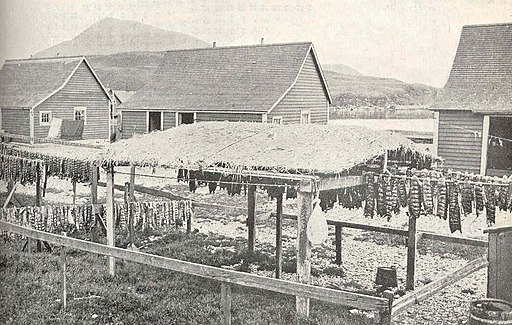

On the islands that lie between Alaska and Russia, ancient tradition mandates that the native Aleut people will not pick a blueberry without ceremony or prayer. In 18th century colonial India, 363 Bishnoi men and women died at the hands of foresters while clinging to their trees to save them from being turned into timber, inspiring the term ‘tree hugger.’

While perhaps not the first that comes to mind, one word to describe these acts is, by definition, ‘stewardship’: the conducting, supervising, or managing of something, especially the careful and responsible management of something entrusted to one’s care.

Echoing Leopold and others who have come before, we at CIFOR-ICRAF, our partners, and the growing global community invested in re-examining the relationship between people and nature are ascribing a contemporary meaning to the concept of ‘stewardship.’ In this understanding, stewardship is the respect we exercise in using nature to produce the goods and services necessary to meet the needs of the world’s 8 billion people as well as those of the environment. It’s clear we must get away from our abusive and purely extractive relationship with nature, and stewardship embodies a responsible and caring relationship with the natural world to ensure collective, planetary well-being and health.

Who are the stewards?

As illustrated in the examples at the beginning of this article, the notion of stewardship of nature is as old as human culture. Today, we think of environmental stewardship as inclusive, equitable, place-based, and focused on resilient, prosperous, and sustainable development.

We can think of stewardship of land in particular as a deliberate and informed combination of solicitude, foresight and skill – a marriage of practice and ethics – that has tangible impacts in landscapes. Present-day movements around regenerative agriculture, natural farming and agroecology, buoyed by attention to gender, ethnic and age equality, are examples of the modern embodiment of stewardship practices at forest, farm and community levels.

Land stewards, then, are not simply owners or producers of commodities (food, timber, fiber, etc.), as water stewards are not just those making use of water resources. Yes, stewards are engaged in their landscapes, but in ways that uphold a ‘duty of care’ – an ethos of responsibility for all the ecosystem services the land currently provides, as well as the integrity of its history and, importantly, its future. This, of course, takes hold best when stewards, as individuals or communities, hold rights to their land and waters, giving them the legal assurance to invest in the longevity of their natural resources.

Supporting these directly engaged stewards are larger players, such as governments, businesses, educational and research institutions, nonprofit organizations, and the slew of others that recognize the societal benefit of environmental stewardship, which fuels their relationship with landscapes and their caretakers with the same mindset and approach of stewardship – in whatever form that may be, from policy support and project implementation, to knowledge and site-specific research, to innovative finance. Establishment of national parks, climate negotiations and public awareness campaigns are all forms of stewardship when executed well, but ideally their missions ultimately tie back to advancing the efforts of the people spending their days working to sustainably benefit from and protect our natural resources.

Stewardship also involves fluid, productive dialogues between all these actors to improve the policies, consumption patterns and behavior change needed to realize sustainable benefits from nature for livelihoods.

Market influence

The market economy and balance sheets require land to be considered as a fixed asset, which in turn implies that market mechanisms can drive sustainable outcomes. But it is this strictly utilitarian view of land and nature that drives their commodification – and the crushing environmental crises that result.

A primary part of the problem is that markets have no realistic way of pricing agricultural commodities so that they bear the full cost of what it takes to ensure land and nature are resilient and able to heal themselves. (Embedded in this is the aforementioned challenge that, in many countries, and especially in forest-reliant communities, insecure or unclear property and tenure rights act as deterrents to investments in stewardship.)

It is no wonder that forests are being replaced by monoculture oil palm, cacao or plantation timber. Even where they exist, the niche markets for high-priced ‘fully costed’ products are far too thin to offer people decent livelihoods and the means to sustain their original landscapes. Farmers in these scenarios are reduced to agricultural factory workers, for lack of a better term.

Over time, the results of these powerful and unsustainable market pressures on direct land users – perhaps would-be stewards under different conditions – result in rapidly degrading land and the ensuing cascade of effects: massive increases in greenhouse gases, disappearing biodiversity, polluted and vanishing water resources, and ever intensifying forms of agriculture that are increasingly dependent on ecologically and economically expensive inputs. This is accelerated by the erosion of social externalities, such as democratic institutions, livelihoods, rights and nutrition.

Turning point

We clearly need a change in direction. We believe the answer lies in a shift to a stewardship economy, which would operate both within and outside markets as we know them, supporting, recruiting and connecting stewards, nature and the broader economy through an equitable and affordable system of incentives and rewards that would assure the future of life as we know it. It would aim to fairly reward farmers, forest users and other ‘landscape architects’ for the produce they deliver to markets. It would also see them profit from the services and values they conserve and restore – clean air, removal of greenhouse gases, clean water, biodiversity, and places of spirituality, worship and history.

As for pricing, commodities in a stewardship economy would bear their fair – but not necessarily full – share of the true costs of their production and trade. This means a kilo of rice, wheat or maize would not be priced out of the grasp of poor people. The difference between these fair and full prices would be paid outside market mechanisms, such as through ‘conditional cash transfers’ that are a recognized mechanism for performance-based payments, in this case used for the delivery of services beyond the produced commodities.

In this way, stewards are not forced to commodify their landscapes, as they are rewarded for allowing their lands to continue in health. The two core pillars of the stewardship economy, then, might well be the total income from fair commodity prices and stewardship dividends – delivered through conditional cash transfers, for instance – for service delivery.

A major task, then, is co-designing the mechanisms and building the institutional architecture that help determine both the fair and full costs, translate the fair costs into market prices, and ensure the equitable difference – what could be called the ‘stewardship dividend’ – is efficiently put into the pockets of stewards.

At the same time, the individual rights of stewards and their communities to land and natural resources would need to be taken into account. Innovative finance and investment arrangements, including peer-to-peer finance systems, would have to be mobilized to achieve this.

We believe almost all the tools and elements of a stewardship economy exist already, in one form or the other; what has been missing has been an effort to put the parts together into a greater whole. Our intention is to explore this assembling in the context of the stewardship of farms, forests and terrestrial landscapes.

Modern forms of agriculture, forest and land management have divorced people from nature. People have been turned into laborers and nature into commodities. ‘Stewardship economics’ is the turning point we propose for a more resilient, equitable and optimistic future. Nature is more than products; it also provides immeasurable services. People are not just producers; they are also caretakers. It is high time we recognize and reward this, and we will all benefit as a result.

Stewardship Economy

An equitable system of exchange that rewards those managing nature sustainably for the goods and services derived from those landscapes – which often feed into markets to meet the needs of the global population – while recognizing and promoting the rights of all people to food, water, nutrition, health, voice and a decent livelihood. Coupled with pillars of the landscape approach and democracy, it builds upon classic notions of ‘stewardship’ in a modern context: a deliberate and informed combination of solicitude, foresight and skill – a marriage of practice and ethics – that brings visible and tangible impacts in landscapes and ecosystems. It is underpinned by economic principles and financial mechanisms that will ensure fair and equal benefits and market inclusion of land managers, while meeting consumers’ pricing needs. Shifting fully to a stewardship economy, which exists today in facets and fragments, can swiftly unblock pathways to a more sustainable future for a planet in crisis.This research forms part of the CGIAR Research Program on Forests, Trees and Agroforestry, which is supported by CGIAR Fund Donors.