Great at creating problems for humanity, fossil fuel giants increase oil demand in the form of plastic.

By Maya Rommwatt, Common Dreams (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).

Oil companies are high on the hog again, with record high gas prices fueling record profits–profits so high they’re even catching the attention of Democrats in Congress. And of course, they’re using the profits to buy back shares so their shareholders will benefit from higher stock prices.

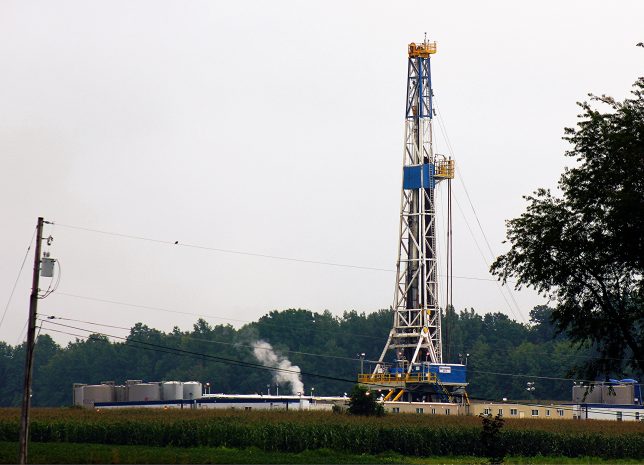

Maybe all that money is going to their heads because only a handful of years have passed since we learned Exxon and many other big oil companies have known since the seventies exactly how their dirty product was about to trigger a global meltdown. Yet they’re still up to their old tricks and trying to fool us while they pump more oil. As governments and communities race to stop runaway climate change, oil companies have quietly found a way to sell even more oil, in the form of plastic. Plastic production is projected to grow astronomically and is expected to account for 60% of oil demand in the next decade.

It would be nice if plastic made from oil was as clean and benign as makers of plastic would like us to believe, but petrochemical plastics are dirty from start to finish, and it’s the product where big oil is placing its largest bets. It turns out some of the biggest oil corporations are also some of the biggest petrochemical corporations. And petrochemical production is mostly plastics.

Cheerleaders of increased plastic production can talk all day about how the solution to the plastic waste crisis is simply more recycling, but less than 9% of plastic is actually recycled, and the industry is now trying to relabel plastic incineration as recycling to help justify increased production. And plastic waste may be just the tip of the iceberg. Before all of the needless plastic products and packaging oil companies make even reach the waste stream, they’ve already done countless damage to communities near sites of production and to consumers.

To make plastic out of oil, petrochemical plants release toxic air pollution that saddles nearby communities with inordinate negative health impacts, communities which are more often likely to be communities of color. If plastic production increases as planned, these communities will be subject to even more dangerous air pollution than they already grapple with.

Once the plastic is made, it enters the market where consumers become the next group of humans put at risk by dirty oil in the form of petrochemical plastic. Unless you live on the dark side of the moon, where presumably it’s not yet a problem, then you’ve probably heard of the microplastics problem. How plastic things fall apart into little pieces, each shred smaller than the last. How scientists can’t seem to find a place on the planet that’s not teeming with microplastics. How scale doesn’t matter because it’s in the air above the tallest mountains, in the streams on every continent, and in our blood and breastmilk. Now that we know it’s everywhere, scientists are beginning to ask if plastic is actually safe, because it’s made with myriad chemicals.

As they examine the toxic impacts of petrochemical plastics, scientists are beginning to warn that it’s not looking good for us. The more research that is done into the impact of plastics on human health, the more that dangers are discovered. Plastic contains many toxic chemicals, and it turns out many of those chemicals are moving from the plastic into our bodies. That plastic soda bottle you drank out of last week? Odds are good that the chemical used as a catalyst in the bottle making process has made its way into the soda. That polyester stuffed animal your infant adorably sucks on the ears of? It’s also made with a dangerous catalyst that may be released into your child’s mouth. Defend Our Health tested beverages in plastic bottles and found dangerous chemicals in every single one, at least one of the chemicals a known carcinogen.

We cannot continue allowing oil companies to poison our air, bodies, and climate with their toxic product. This is a critical moment in history, and when they’re not too busy reaping outrageous profits, oil companies are trying to convince us the product they’re selling isn’t killing the planet and everything on it, despite the evidence. Instead of making more stuff we don’t need, like a box full of air-filled plastic bubbles that take up nine-tenths of the box space because it was somehow cheaper for Amazon to mail a thing that way, perhaps the industry could check the room and start trying in earnest to transition itself off its dirty product. You’d think none of these companies would want to be the last one around trying to sell a product no one wants, but it seems they’re all participating in a mass delusion driven by short-term thinking. It’s time to draw down, not ramp up, oil and gas, and that means plastic production too.